The Religious Regression of Gender Equity in the Philippines

I created this exhibit because of how Catholicism is integrated into the lives of everyone I know as a Filipino. It influences our daily routines, the family dynamic, how we behave, and our pattern of thoughts. I read that before the Philippines got colonized by the Spaniards it was a matriarchal city-state society, in which gender equity was practiced and enforced, as well as sexual freedom. I got incredibly curious about how such a progressive society, regressed towards a patriarchal heteronormative one to the point that women were confined to live with no bodily autonomy or economic freedom. With this exhibit, my aim is to pinpoint the actions or systemic implementations that led to this result, as well as share some minute but persistent resistance in the midst of this cultural erasure. I aim that the general audience, people who come across this by chance, learn the dangers of abusing religion and unravel the thread of how colonialism still maintains its impact to this day.

This photo encapsulates the origins of people in the Philippines. The Kalinga tribe is known for having the last remnants of a specific art of tattooing, called Batok. In terms of sex and gender, they were used as symbols of coming of age. For men, it was seen as them becoming a Kalinga warrior. For women, it was seen as them becoming fertile and mature. This image of two young girls from the Kalinga tribe signifies the preservation of the Philippines’ native roots. The way that tribal religions like the Kalinga tribe, believe in representative tattoos to symbolize the bodily autonomy of their coming of age pushes forward the progressive idea of consent and growth.

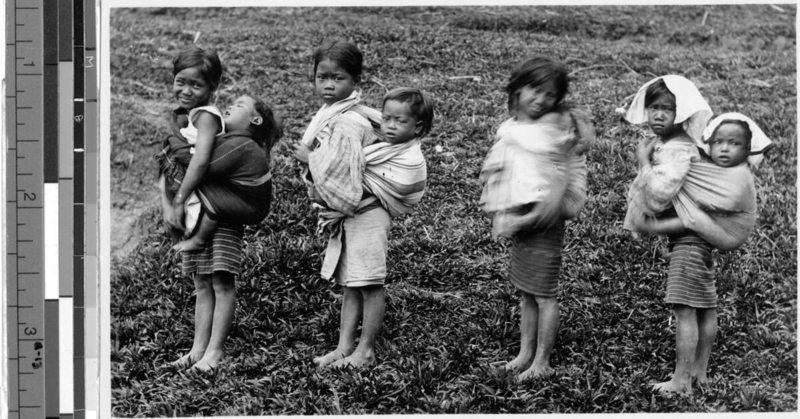

These girls represent how the responsibility of filial piety is implemented in the lives of young children from a very young age. A way that this contributes to the topic is how matriarchal responsibility is subtly enforced, not for maternal reasons, but because of the familial expectation to adapt to changes in traditional family structures. This artifact represents how domestic familial work represents entire communities, by starting within the family. Women now leave their families for domestic work abroad to provide them financial support, leading familial responsibilities to either shift towards the father, the aunt or uncle, or even godparents in some cases. Nonetheless, the “maternal” role transcends gender underlining its importance. In relation to other artifacts, it embraces the power of domestic influence in a way that puts filial piety first which also instills gender equity.

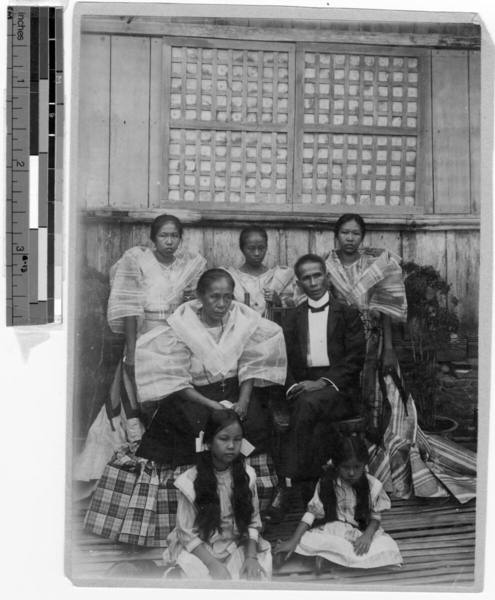

This is the Philippines' take on the nuclear family, in which Catholicism shaped it to be patriarchal. It contributes to the topics of gender roles and sexuality through how Catholicism confined women to taking care of household chores and familial duties, enforcing an image in which Filipina women were submissive and weak. In the description, the mother wears a rosary around her neck which can also symbolize the quiet control religion has on her self-determination. In relation to other artifacts it also pinpoints the idealized control colonialism implemented through Catholicism, in which men were the heads of their family and women were only meant to birth and take care of their children.

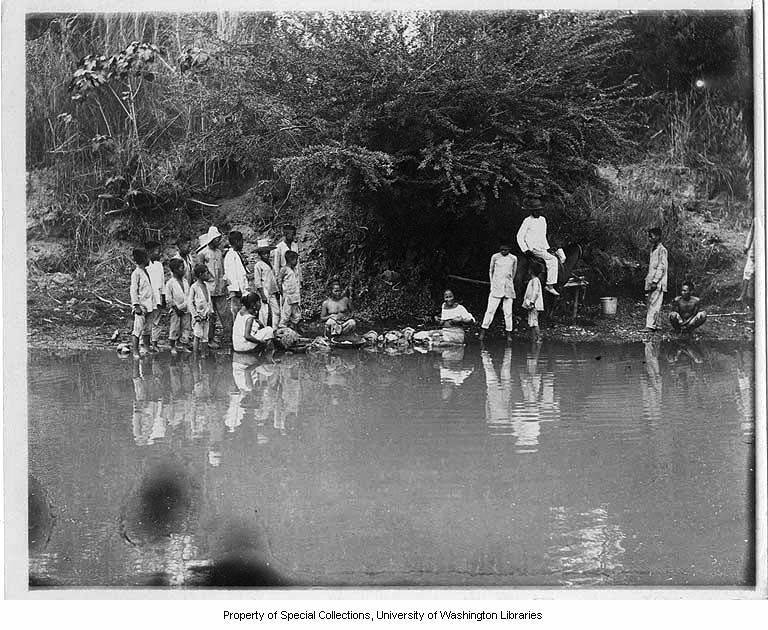

This is an age-old practice called Labada which still is present to this day. How it contributes to colonial regression gender inequality is how one of the many roles women in a Filipino household had was and is to clean, mostly enforced by their mothers in order to become good housewives. But while they do perform those duties they often use the river as a spot to meet and socialize. This photo is an example of that socialization, in which they often talk about their ideas and problems, as well as self reflect with each other. In many ways, Labada anchored their identities. Not because of the chores that they’re given, but the company of the minds that they’re with.

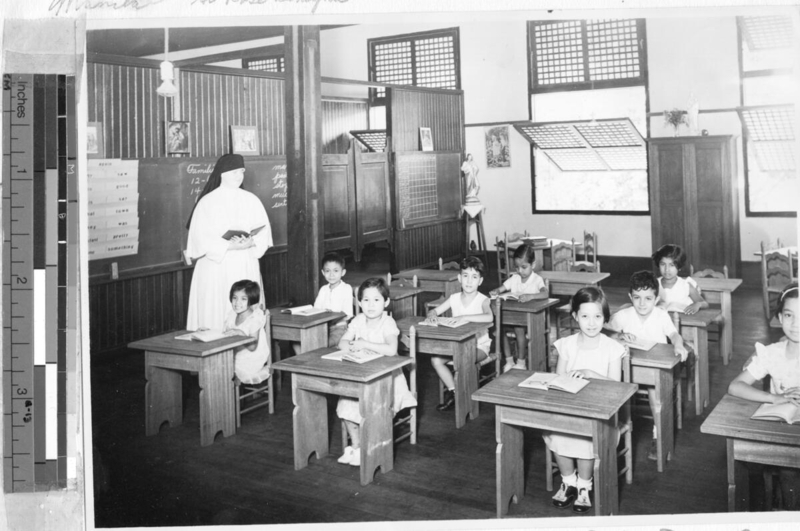

This artifact shows how the enforcement of gender roles and the erasement of cultural identity was also done through education. It contributes to how cultural degradation and patriarchal roles were enforced within the school’s curriculum, influencing young impressionable minds, causing them to put their “education” first instead of their cultural roots. This artifact, in which a white nun is in charge of the education of young Filipino children, very much signifies historical themes of a “white man’s burden”, underlining the cunning infrastructure of cultural erasure, which coerced children into submitting to a culture that degrades their origins.

This novel symbolized an act of revitalization of rights within the Philippines, which pertained to all genders. It addressed the injustice Filipinos experienced due to colonization, in which friars and nuns would abuse citizens for not staying in “line”. It addresses the active resistance Filipinos had, which sparked the Philippine revolution as well as the movement to erase the effects of colonialism. This artifact was written by a man named Jose P. Rizal, he was a talented scholar whose book Noli Me Tangere signified Filipino ideals. This marks the active take-back of the Philippine’s cultural identity, which was sparked by an earnest scholar.

Maria Clara, a character from Jose P. Rizal’s novel Noli Me Tangere, was a cult figure. She symbolized Filipina ideals, which were to be virtuous and demure. Many used Maria Clara to amplify the preexisting sexist and repressive views of Filipina women. This led to the backlash of many women who rejected the regressive symbolism she brought, leading a generation of women poets to question their place in society as well as sexuality. This artifact shows the lack of progression in gender equity and sexuality movements after the Philippine revolution. It marks the importance of societal figures that are used to push forth a colonial mindset, bringing harm to gender equity and sexual liberation.

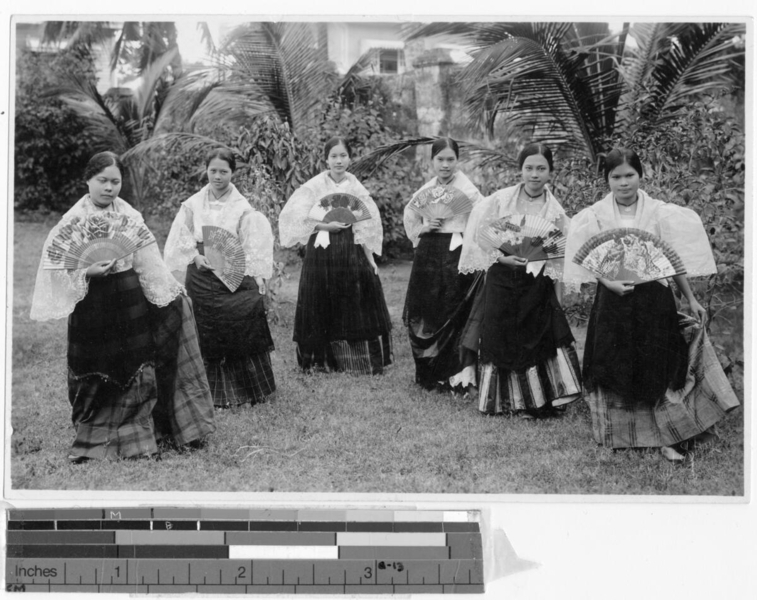

In the 1930s, nursing became the primary reason as to why women wanted to pursue an education. It allowed them to have economic independence and opportunity, and a way to leave the house-wife dynamic predetermined by their families. It allowed Filipina women some semblance of self-determination, which was a step forward towards gender equity and sexual liberation. This artifact in a way is a family portrait, in which like-minded individuals celebrate their own educational achievements and economic opportunity. It marks the first stride towards independence, which will eventually unravel into a women’s movement in the 1960s.

In all, colonialism has been reduced to guns, germs, and steel without regards to subconscious inequity that remains today. It almost never addresses religion, which is often used as a double edged sword, contributing to the erasing and degrading of one’s culture. Although colonialism seems to have taken place many years ago, its identity still lives to this day.

About the Curator:

Chelsey Ficke was born in Connecticut of all places in 2002. When she was 6 months old she and her family moved to Tokyo, Japan. She grew up in an all-girls multi-cultural Catholic school before moving to Washington state in 2016. Growing up, she was an inquisitive kid who often asked too many questions. She always wondered why the status-quo was the status-quo, especially when it was a detriment to who she was. Later on, this curiosity has developed into a love for history and social movements. She's always willing to try new things and aspires to always keep learning (and unlearning).

Archives:

University of Southern California, Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America Archives

University of Washington, International Collections Archives

University of Santo Tomas, Miguel De Benavides Library and Archives

Works Cited

Hutton, Belle. “The Last Tattooed Women of the Philippines' Kalinga Tribe.” AnOther, AnOther Magazine, 26 June 2018, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/10962/the-last-tattooed-women-of-the-philippines-kalinga-tribe.

Estrelloso, Cecile, et al. “Peer Reviewed Journals, Open Access Journals: International Journal of Advanced Research (IJAR).” International Journal of Advanced Research, Ijar, 26 Feb. 2022, https://www.journalijar.com/.

Asis, Zea. “Why It's Time to Rewrite María Clara & Our Filipina Story.” Cambio & Co., Cambio & Co., 2022, https://www.shopcambio.co/blogs/news/why-it-s-time-to-rewrite-maria-clara-our-filipina-story.

Razón Félix, and Richard Hensman. The Oppression of the Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 1976.

Claudio, Lisandro E. Jose Rizal: Liberalism and the Paradox of Coloniality. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.