Women in Indonesia

Strength and Power

By Mali Rajsavong & Joshua Calayan

We've produced this exhibit to acknowledge the unrecognized and underrepresented women of Indonesia. Throughout our middle and high school journeys, we have not studied much Southeast Asian history, nonetheless Indonesian history. There are many untold stories of women experiencing hardships through feminism, as well as hidden achievements. Indonesian women used different strategies and social justice actions to combat different forms of oppression. The tactics that men and society use against Indonesian women are largely based on gender, sexuality, religion, race, and ethnicity. These characteristics along with many others provide an intersectional outlook on how feminism takes place in Indonesia and all over the world.

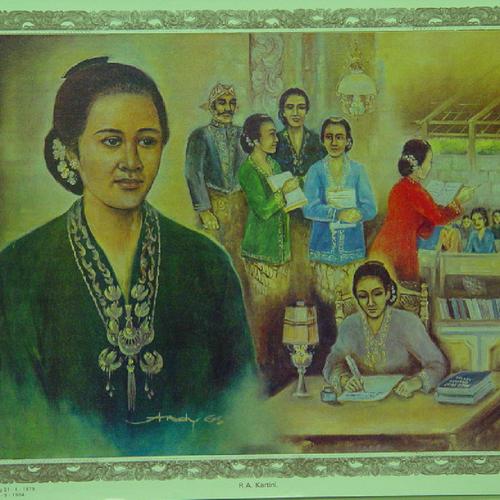

Raden Adjeng Kartini (artifact #1) also known as R.A. Kartini was an Indonesian activist who fought for both women’s rights and education. Living from 1879 to 1904, a time when the Dutch were using Indonesia for its natural resources, Kartini wanted to make women more prevalent in Indonesia’s educational system, creating a school plan for girls to have the same education as boys. She was also concerned about the health system and medical care, especially for women. In order to enact her plan and make Indonesia a better place, she studied in the Netherlands before coming back and opening a school for women. By improving the educational and medical system for girls, Kartini would affect Indonesia’s future long after she died when women would achieve equal rights in 1945.

Cut Nyak Dhien (artifact #2) was an influential military leader in Indonesia who grew up in a traditional Islamic household, and was taught domestic tasks as a woman. Dutch military forces invaded Indonesia in 1873, starting the Aceh War. Dhien’s husband and father held high-ranking military positions and were killed during the battle. To avenge her father, husband, and homeland, Dhien took her husband’s position and led the Acehnese guerilla forces. As Acehnese military families grew, they had more military forces and advanced their group of spies. Dhien was eventually caught and exiled to Sumedang, an island of Java, Indonesia. She kept her identity hidden, while she and the Aceh rebellion fought until the very end when the Dutch took complete control in 1904. On May 2, 1964, Cut Nyak Dhien was named a national hero of Indonesia.

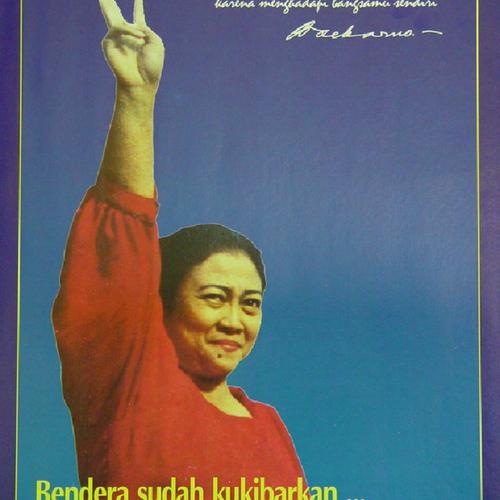

This poster depicts Megawati Sukarnoputri (artifact #3), the 5th president of Indonesia. Sukarnoputri is also the first female president so far, serving in office from 2001-2004. During this time, she was known for stabilizing Indonesia’s politics through fixing the relationships with the three government branches. Between her times as a politician, both before and after her presidency, she has been involved in several important discussions in Indonesia, such as the more recent relocation of Indonesia’s capital. To this day, Sukarnoputri still has influences on the Indonesian government.

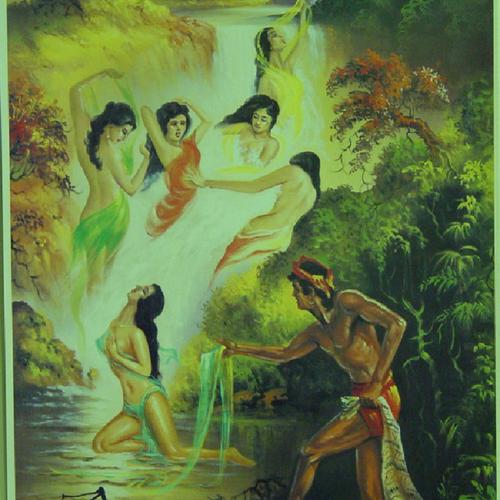

Folktales and mythology are the main storytelling forms in Indonesia. In Central Java, Indonesia, the ancient folktale Jaka Tarub (artifact #4) is one of the most well-known tales and was produced with a very Westernized plot. In the tale, after a woman named Nawang Wulan is saved and then married to Jaka Tarub, she keeps her true powers unrevealed. The special ability she holds is to cook only one rice grain every day, but it multiplies into many for her whole family to eat. Jaka questions her power and investigates his wife which causes a disturbance in her abilities. Nawang quickly realizes that her husband betrayed her trust and leaves the marriage. Despite his protests and begging, Nawang leaves because she sees that she can be just as powerful without him. Historical folktales as such tend to oversexualize women and compare femininity to masculinity in very traditional ways. Nawang is painted as a woman who is alluring and seductive and follows her husband’s orders when she already has superior power. There have been many interpretations of this folktale over time, but one trending theme in recent works is that women are rewriting the mythology to show the trauma women go through.

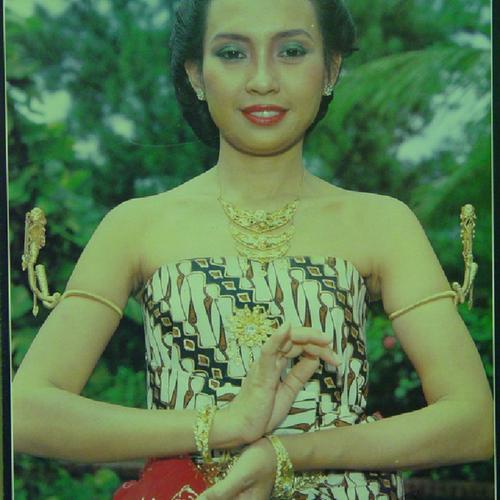

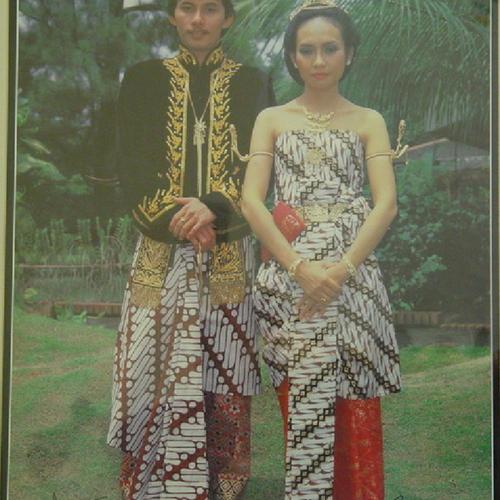

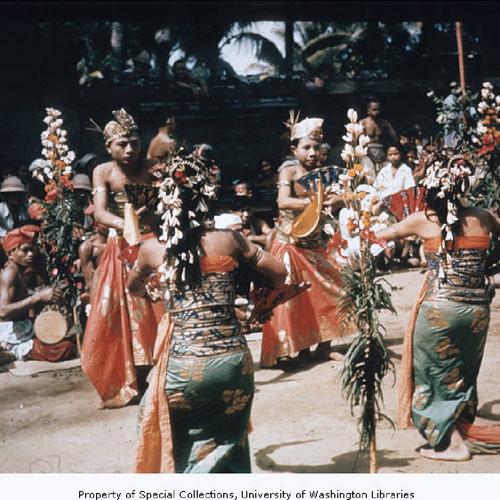

Plays and Javanese dramas also play a large role in how women are perceived in Indonesian culture (artifacts #5, #6). There is constant discussion about the concept of what an “ideal” woman is in Javanese culture. When men narrate stories in scripts and literature, they do not accurately depict the lives of women. Although performance arts in Indonesia is a commanding art form, it is a very male-dominated field. Feminist writers express their anger and distaste towards men in new compositions. Additionally, the Balinese Dance is a cultural performance (artifact #7) that is an ancient tradition that can come in many different forms, from the Sanghyang Dedari dance that is used to counteract level spirits, to the Joged Bumbung variant that is done by couples during harvest season or on important days. These stories and dances are tied back to Hindu rituals and sacred dances done with the Balinese communities, carrying on and being an important part of the Indonesian people of Bali's lives. Not only do women and couples perform Balinese dances, but queer and trans individuals in Indonesia do as well. The women and LGBTQ+ community in Indonesia performed Balinese dances as a form of protest against colonialism. These dances were a way to maintain dimension and embodiment in their beings.

As creators of this exhibit, we want to focus attention on the marginalized women of this region. There are many women in Indonesia and surrounding territories who showcase hardworking feminism but are not recorded in history. The mapping of immigrant journeys (artifact #8) highlights how many of our histories have feminist work in the Southeast Asian region. With many different paths indicated on the map, it is clear that we should continue to conversate about women within social movements and unheard stories from all over the world. Throughout this exhibit, we have seen how Indonesian women have gotten their voices heard. By stepping out of the gender norms of their culture, they have shown that women are just as capable as men.

Citations

Cut Nyak Dhien. (2018). In J. Mellors (Ed.), Encyclopedia of World Biography (2nd ed., Vol. 38, pp. 70-71). Gale. https://link-gale-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/apps/doc/CX3669500040/AONE?u=wash_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=6aed4b0e

Dewajati, C. (2007). Indonesia. In S. Joseph (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures (Vol. 5, pp. 412-416). Brill Academic Publishers. https://link-gale-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/apps/doc/CX2686501409/GVRL?u=wash_main&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=4073cd7f

“Kartini in Her Own Words.” (2021). Inside Indonesia, www.insideindonesia.org/archive/articles/kartini-in-her-own-words.

Kristianto, Y. (2023). “Balinese Dance History: Tracing the Steps of Tradition.” Balienza, balienza.com/balinese-dance/.

Rahayu, L. M., Priyatna, A., & Budhyono, R. (2018). Reinterpretation and Reconstruction of the Folktale Jaka Tarub into Akhudiat’s Play Jaka Tarub: A New Historicist Reading. KnE Social Sciences, 3(9), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v3i9.2606

Storti, A. M. M. (2023). A Case for the Two-Dimensional: Balinese Dance, Colonial Shadows, and Feeling Otherwise with Zavé Martohardjono. Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas, 7(3), 267–292. https://doi.org/10.1163/23523085-07010005

SYAFPUTRI, E. (2014). “The History of Balinese Dance.” Tempo, TEMPO.CO, en.tempo.co/read/555872/the-history-of-balinese-dance.

Ziegenhain, P. (2008). The Indonesian Parliament and Democratization. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, (Page 146)

Archive Links

University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections

About the Curators

Mali Rajsavong (she/her/hers): I am a first-generation Southeast Asian American college student at the University of Washington Bothell, majoring in Media and Communication Studies and minoring in Diversity Studies. I took this GWS class as an opportunity to broaden my scholarship in a subject that I am new to. I am happy I took this class with Dr. Shayne seeing as I have gained more knowledge and perspectives on feminism in such an insightful way. Outside of this classroom, I intend to use the understanding of complex topics that I've acquired to advocate for the continuous growth of feminist knowledge production and work.

Joshua Calayan (he/him/his): I am a student at UW Bothell and am majoring in Computer Science and Software Engineering. I took this class because I was fascinated by a GWS class I took previously and wanted to know more about how the LGBTQ+ community is persevering. This class helped me get a wider grasp on the history of these struggles, and I've had a good time learning about the history of all these different communities that have fought and survived against all the odds stacked against them. I'm not exactly sure what I plan to do with this outside of the classroom, but I still feel like it is an important piece of knowledge that I should have.